The Hyde Continuum: From Colonial Power to Modern Nationhood

- Sylvian Hyde

- Aug 10, 2025

- 5 min read

Introduction: The Bigger Picture

Parts 1 and 2 explored the hidden story of George Hyde, his 1827 petition for equal rights, and his father James Hyde’s powerful role as Agent of British Honduras. Part 3 looks beyond the personal histories to see the larger continuum, from the Hydes’ strategic moves in the colonial era, to regional shifts across the Caribbean, to the modern revival of a legacy that still shapes Belize today.

1. Succession of Influence

The Hydes were more than a wealthy family. They stood at the intersection of commerce and governance. James Hyde, as Agent of British Honduras, had direct access to the British Colonial Office, the imperial nerve center for policy. His recommendations often became the Superintendent’s marching orders in Belize, giving him indirect but substantial control over the colony’s direction.

George Hyde inherited not only his father’s wealth but also his political insight. His 1827 petition challenged racial laws that excluded free-coloured men from holding office, serving as magistrates, or obtaining military commissions. Together, father and son created a succession of influence:

James Hyde (1820s): Guarded economic strongholds like Lamanai, influenced trade and law at the highest levels.

George Hyde (1827): Pressed for political inclusion, paving the way for dismantling racial barriers.

Post-Emancipation Leaders (mid–late 1800s): Benefited from reforms that opened leadership to people of African and mixed descent.

Independence Leaders (1960s–1980s): Operated in a political framework partially built by the Hydes’ fight for equality.

2. Economic Continuity and the Lamanai Stronghold

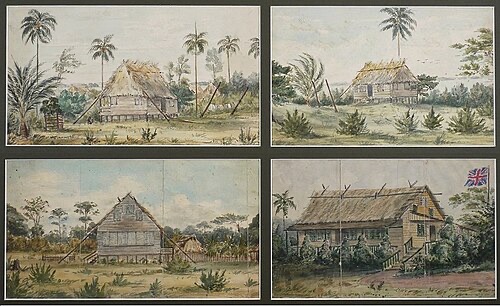

Lamanai was more than a plantation. It was a multi-era economic powerhouse. Occupied for over 3,000 years, from the Preclassic Maya era through British colonial rule, its location along the New River controlled inland–coastal trade routes, fertile farmland, and access to mahogany and logwood extraction zones.

In 1827, defending Lamanai was not just about land ownership. It was about safeguarding the colony’s agricultural output, timber exports, and transport infrastructure. Control of Lamanai meant influence over Belize’s fiscal stability, an economic stability later inherited by an independent Belize.

3. Regional Context and Strategic Foresight

The early 1800s saw sweeping changes in the British Caribbean. Free-coloured elites in Jamaica, Barbados, and Trinidad were petitioning for equal rights. Slave uprisings, coupled with Britain’s abolition of the slave trade in 1807, signaled the decline of the old plantation order.

James Hyde, positioned in London with his finger on the imperial pulse, would have recognized that Belize’s timber economy was nearing its peak. He also knew that the racial and political structure of the Empire was shifting. Securing key assets and supporting George’s fight for inclusion was a way of future-proofing the Hyde legacy in anticipation of a post-slavery, more inclusive era.

George’s petition was not just a personal plea. It was a strategic move to ensure the family could directly hold leadership roles when the political order inevitably evolved.

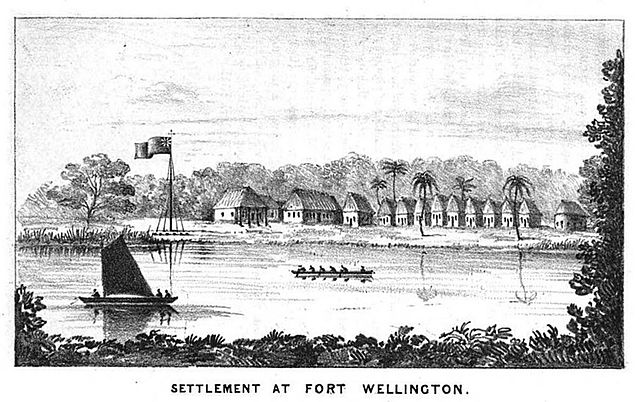

4. The Mosquito Coast Connection

The British evacuation of settlers from the Mosquito Shore in 1786 brought a wave of people, influence, and alliances into Belize. Among them were families whose descendants would shape Belize’s southern districts, including Punta Gorda. The death of the Mosquito King and the reconfiguration of British–Mosquito alliances played into this migration, bringing political and commercial experience that would help define the region.

This connection runs directly to me. Through my maternal lineage, from my great-grandmother Lucille Melendrez, revered as the matriarch of her community, founder of the People’s United Party Women’s Group, and honored with a boulevard named after her in the heart of Punta Gorda, I carry forward a tradition of leadership and service. She mobilized women, shaped political discourse in southern Belize, and nurtured her community as a mother figure whose influence was felt across generations.

That same spirit of diplomacy, economic vision, and nation-building flows in me today. This heritage is not just history, it is living influence. I carry it forward in my work to strengthen Belize’s economic and diplomatic position in the world.

5. The “What If” Counterfactual

Had James Hyde not supported George’s demand for equal rights, had he chosen to uphold the racial order of the time, the road to Belizean independence might have been delayed by decades. Without early reforms, the rise of leaders like George Cadle Price, and the diversification of leadership across race and class, could have been stalled.

Who knows when that path would have begun, or whether anyone else would have had the heart, resources, and connections to set it in motion?

6. Modern Currency, National Heroes, and the Question of Legacy

In 2025, Belize updated its currency to feature national heroes such as George Cadle Price. While Price’s role in independence is undeniable, the groundwork for Belize’s economy and inclusive politics was laid long before.

If nationhood is the ability to control one’s economy, governance, and future, then the Hydes’ defense of strategic land, influence over colonial policy, and dismantling of racial restrictions in the 1820s were foundational. They were part of the imperial machinery but saw that an independent future was coming, and acted to secure their place in it.

7. The Baymen Legacy and the 386-Year Continuum

This legacy does not begin with James Hyde in the 1820s. It reaches back to 1638, when the first Baymen, British woodcutters and privateers, settled along the Belizean coast. These British subjects forged early alliances with the Maya for trade, protection, and mutual benefit.

They were more than opportunists. The Baymen formed a cooperative, self-defending community whose governance and identity laid the groundwork for Belize’s distinct culture. They resisted Spanish incursions, operated under their own codes, later formalized as Burnaby’s Code in 1765, and built the timber trade that would define the settlement’s economy for over a century.

By the time James Hyde became Agent of British Honduras, the Baymen tradition was already nearly two centuries old. He inherited, and helped formalize, what the Baymen had built: a British-protected, self-governing settlement sustained by commerce, intercultural alliances, and the spirit of economic resilience and self-determination.

From the Baymen to James Hyde’s role in imperial governance, to George Hyde’s push for political inclusion, to the Mosquito Coast influence in the south, and now to my leadership, this is an unbroken chain, the essence of a 386-year-old living heritage.

8. The Modern Legacy and My Marquis Who’s Who Recognition

Today, I carry forward the Hyde legacy through the revival of a 386-year-old heritage brand with both economic and diplomatic potential for Belize. I am the modern link in this continuum, reawakening the same vision and strategic action that defined my forefathers.

What I am building today is not just a business, it is the rebirth of a vision and a spirit that have guided my family for centuries.

In 2025, I was honored with a place in Marquis Who’s Who in America. This is not an accolade you can buy, it is recognition that must be earned. To me, it is more than a personal achievement, it is international acknowledgment of my place in this lineage. That it comes here in New York City, the world’s financial capital, the fashion capital, and the home of the United Nations, is deeply symbolic. It is the perfect stage for Belize’s story to be reborn and shared with the world.

Citations

CO 123/18/3 – Memorial of James Hyde regarding the estate of Lamanai (1827)

CO 123/18/9 – Memorial of James Hyde, Agent of British Honduras (1827)

CO 123/27/47 – Petition of certain free persons of colour in Honduras (1831)

Alfred E. G. Gibb, British Honduras: A Historical and Descriptive Account (1883), Internet Archive

Melissa A. Johnson, The Making of Race and Place in Nineteenth-Century British Honduras (2003)

Bridget Brereton, “Colour, Class and Politics in Trinidad, 1830–1940,” Journal of Caribbean History, 2002

Comments